All The More Dangerous: Taking Care in Uncomfortable Theatre

The first time I read Paula Vogel's Pulitzer Award-winning play, How I Learned to Drive, I was having a bad day. I felt frazzled and let down by my community. I had a few conversations before I started to read, and when I mentioned I was about to begin How I Learned to Drive, most people said something the along the lines of "oh, you're going to read that now?" I knew the play was about pedophilia, sexual abuse, and generally skin-crawling topics. But one friend, after his initial reaction, said that Paula Vogel takes care of you, despite the discomfort. There is something to gain by reading the piece.

Surely enough, after reading How I Learned to Drive, in spite of everything I gasped and grimaced at, I felt calmer. I could engage with the themes and topics of the play without feeling like I was going to be sick. In short, Paula Vogel had indeed taken care of me. I have not stopped thinking about comfort in theatre since.

As young theatre makers and consumers, we are encouraged to take risks and embrace discomfort. But this, of course, is vague. When does discomfort stop adding meaning to a piece? When does a certain risk go too far and ruin what the piece is actually trying to say?

I think of The recent Broadway production of 1984, which often popped up in discussions and news for its extreme reenactments of violent torture. Many criticized this aspect of the production, labelling it "torture porn" where the violence becomes a spectacle fetishizing violence to the point the meaning gets lost.

One of the directors, Duncan Macmillan, defended the torture scenes: "We’re not trying to be willfully assaultive or exploitatively shock people, but there’s nothing here or in the disturbing novel that isn’t happening right now, somewhere around the world: People are being detained without trial, tortured and executed. We can sanitize that and make people feel comforted, or we can simply present it without commentary and allow it to speak for itself."

Fellow director Robert Icke says, "There’s an assumption that theater is always safe and comfortable; it’s never that scary, it’s just 'theater scary.' This is designed to hit you hard - please take that [warning] seriously."

Now, I haven't seen 1984, and I think the team of the show makes honest, thought-provoking points. But I think the sheer reaction to the violence speaks miles more than the intention: the thing most people are taking away from the production is "I almost fainted because I was watching someone get tortured on stage." No matter what the intention, that's what everyone has been talking about. The failure to take care of the audience results in a blurring of the message.

Taking care of artists and audiences in theatre is not shielding them from discomfort. It is not censoring and filtering out anything provocative and difficult. It is finding a way to discuss difficult topics and present uncomfortable events on stage that provides enough safety so the audience can engage with the meaning and take something forward. How exactly this manifests depends on the individual piece and production.

We can take cues from How I Learned to Drive: Li'l Bit is played primarily by an adult woman in her thirties to forties, even though throughout most of the action she is in her teens. Vogel presses that the Teenage Greek Chorus, who plays an eleven-year-old Li'l Bit in one of the final scenes, should be played by an actress who is twenty-one to twenty-five because "if the actor is too young, the audience may feel uncomfortable." Very little explicit sexual abuse happens on stage, and even when it does, Vogel is deliberate in when and how. For instance, the opening scene features the two actors sitting next to one another, facing forward, never actually touching one another despite what is actually happening.

That's because, at the end of the day, How I Learned to Drive isn't about the shock value of a teenager experiencing sexual abuse. It is about trauma and empathy, the messiness of trying to process sexual abuse. There is plenty in the play that might make the audience squirm, but there's just as much to make the audience think and feel.

I believe Paula Vogel is a model for how to approach discomfort in theatre, with care and awareness of the audience and actors alike. Through this deliberate care, she is able create pieces that tackle major issues in effective and affecting ways. "I want to seduce the audience," she says. "If they can go along for a ride they wouldn't ordinarily take, or don't even know they're taking, then they might see highly charged political issues in a new and unexpected way...The theatre is now so afraid to face its social demons that we've given that responsibility over to film. But it will always be harder to deal with certain issues in the theatre. The live event - being watched by people as we watch - makes it seem all the more dangerous."

On the topic of physical danger, similar ideas apply. I was speaking to one of my friends, a director, who told me that she wants a true sense of danger in her work, the sense that something could go terribly, terribly wrong. One of these moments in question was the idea of an actress moving around the space with her eyes closed as the set changed around her. But, at the same time as that danger, there is care - a rope on the ground would provide a path for the actress to walk, and the set movement would be carefully choreographed and rehearsed. Simply put, the key to performing danger in theatre is safety. No one should actually be getting hurt on stage, but carefully directed danger makes the audience lean in.

The same goes for moments of intimacy. The rise of intimacy directors is a promising development - it has become vital that should actors need to do anything from a simple kiss on the lips to a full-on sex scene, these moments are carefully choreographed with a focus on mechanics, safety, and consent above all else. Throwing actors into intimate scenes simply does not work anymore - it is uncomfortable for them, and it will be uncomfortable for any audience that witnesses it to the point that they will not be able to think of anything else.

The fact that theatre is comprised of real live people watching real live people do real live things provides a challenge to staging uncomfortable topics and events. Our theatre should engage with human problems: from racism, to sexual assault, to violence. We should not ignore these things because they are hard and difficult to put in front of people. But we must take care. We must take care to present ideas so that they are not appearing for sheer shock value but to provoke thought and emotion from audiences. We must take care in staging violence and intimacy, receiving consent from actors and prioritizing safety. We must take care so that our work can be all the more dangerous.

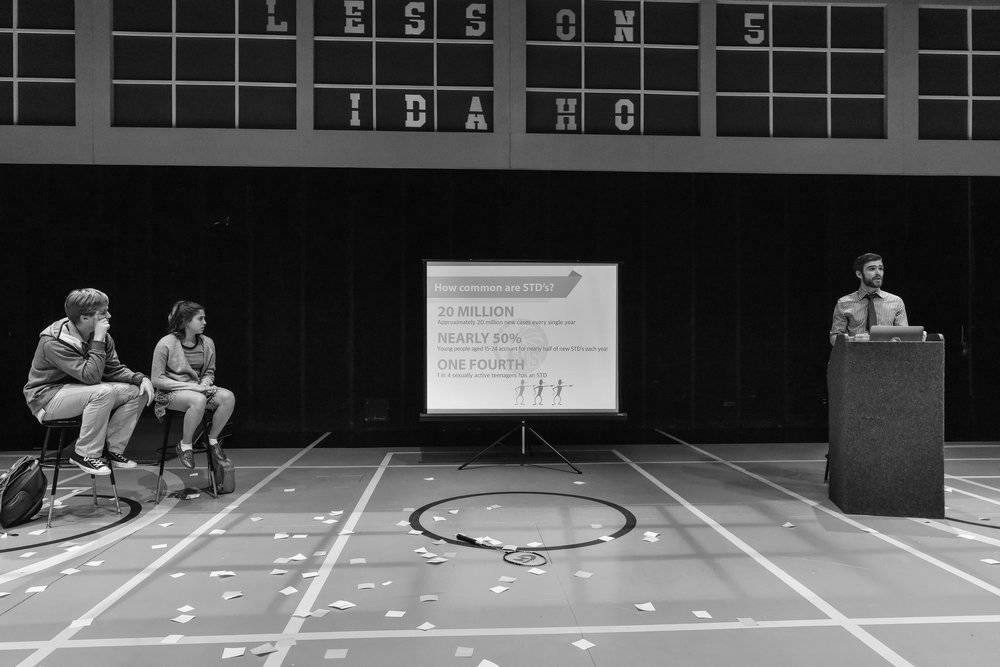

(Photo: Alyssa Wilmoth Keegan and Peter O’Connor in How I Learned to Drive at Round House Theatre. Photo by Kaley Etzkorn.)