The Writing on the Wall: The Use of Brownface in Theatre

By Aditi Kharod

Aditi Kharod is a political science student who frequently uses her identity as a second-generation Indian immigrant as a lens with which to view the world. She loves singing and dancing, as well as (obviously) plays and musicals, but her favorite place in the theatre is a seat in the audience.

In my sophomore year of high school, I was in the ensemble of our school’s production of Legally Blonde: The Musical. There is a South Asian role in that musical: Sundeep Agrawal Padamadan, Elle’s fellow Harvard student and the ex-monarch of a presumably India-like country that is never named—what my friends and I like to call “geographically untraceable.”

A white boy was cast in that role.

Our director had two options: slightly alter the character to be a monarch from a region where the ruler would believably be white, such as Eastern Europe—an uncomfortable option that would highlight how little diversity we had in our school—or make no changes and force the actor to use brownface—a horrifically offensive and outdated option.

Our director chose the latter.

Most of the cast and crew recognized that this was problematic, but did little to nothing to actually ameliorate the issue. This includes myself, unfortunately; none of us had enough courage to confront our director, the only adult in charge of the show, and tell her that she was being offensive.

This wasn’t the worst example of brownface in the world. Sundeep Padamadan is a bit part who has maybe five lines in total and is there solely for comedic relief. Altering the character to fit the actor, while not a completely satisfactory solution, would have been fine for that part, especially for a high school show.

On Broadway, however, the situation is a little different. There is no dearth of diversity in audition rooms, and parts are being written for people of color. On Broadway, we should be altering the actor to fit the character. This is what should have happened in the 2012 revival of The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Rupert Holmes’ Drood is one of my favorite musicals. It is smart, funny, and surprisingly politically aware considering the source from whence it came. The Mystery of Edwin Drood is based off a Charles Dickens novel of the same name. Dickens died before he could finish the novel, so at each show, the ending is left up to the audience’s interpretation. This 1860 novel offers a commentary of colonialism that, had it been published, would almost certainly have been deeply controversial.

In 1835, the British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay described the British territories of South Asia as “ignorant and barbarous,” and wrote various essays proclaiming that without British intervention and education, the “inferior” people living there were likely to remain savages forever. Charles Dickens directly contracted this notion by writing two of my favorite literary characters: Neville and Helena Landless.

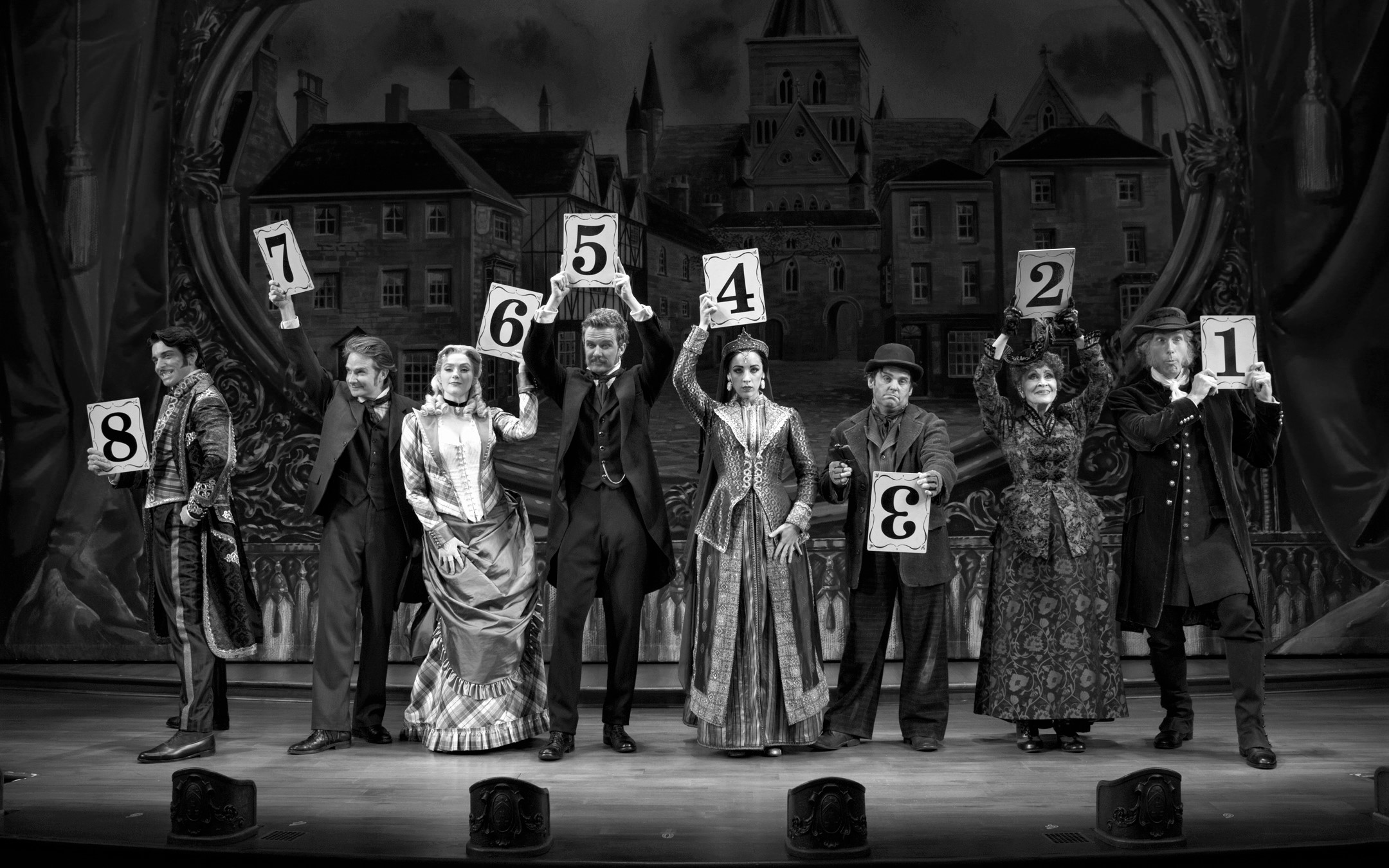

Through the course of the narrative, these twins move from British Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) to Dickens’ fictional town of Cloisterham, and waste no opportunity to offer fiercely witty commentary on the status of being a British subject—there is even a song dedicated to the British hypocrisy toward and oppression of South Asia. These anti-colonialist themes make it especially important that the Landlesses be portrayed by South Asian actors. Unfortunately, in the 2012 revival, Helena and Neville were played by Jessie Mueller and Andy Karl.

In this show, altering the characters to fit the actors wasn’t even a faint possibility. Don’t get me wrong—I love both these actors. They are some of my favorite actors on and off Broadway. But they were not the right choice to play Helena and Neville Landless. Not only did Mueller and Karl put on a thick layer of amber-toned makeup, they also sang in terrible, barely comprehensible, “geographically untraceable” accents and performed some extremely stereotypical choreography consisting of a lot of head bobs and folded hands—although the latter, I know, was not their decision. In short, their portrayal was offensive, made even more so by their fake, brown faces.

The use of brownface, I believe, stems from a systemic lack of representation. Only recently have there been any South Asian actors on Broadway that fans can recall by name - Shoba Narayan comes to mind. Shows touted for their diversity, such as Hamilton, are filled with mostly Black and Latinx actors.

As a society, we have collectively decided, and correctly so, that blackface is offensive. We remember its long history, beginning with minstrelsy, marked by humiliation and degradation of African-Americans, and have erased any traces of it from modern theatre. And while South Asians have not been subjected to anywhere near the same level of oppression, the principle is still the same: brownface is a form of erasure that perpetuates racism and undermines Broadway’s journey toward diversity.

If Broadway truly wants to be more progressive, maybe they should spend less time yelling “F**k Trump” at the Tonys and more time finding diverse actors of all races.

(Photo credit Joan Marcus)