Where are Broadway's Female Creative Teams?

On April 30th, Hadestown was nominated for 14 Tony Awards. Among these were Best Direction for Rachel Chavkin, as well as Best Score and Best Book, both for Anaïs Mitchell. Chavkin was the only woman nominated in her category, and only one other woman – Dominique Morisseau, Ain’t Too Proud – was nominated for the writing of a musical, book or score. It’s not just the creative nominations that are lacking: Hadestown is the only new musical this season with a female director. And it’s the first musical in a decade with a woman as the solo writer.

In the 2017-2018 season, out of all shows on Broadway, new and old, plays and musicals, 19% of these were directed by women. 18% were choregraphed by women. 16% were written by women. Broadway creative teams – directors, playwrights, book writers, lyricists, composers, and choreographers – are overwhelmingly male. All this is troubling because it means that on a fundamental level, women are not telling stories on the most prominent stages available. Too often, even when stories about women make it to the Broadway stage, they are written and directed by men.

It’s not an unknown problem, either. Just about every spring when Tony nominations come out, so do a flood of people pointing out a lack of diversity – and creative awards are a common target. Rachel Chavkin recently told the Associated Press, “One of the oldest truths is that a woman or artist of color has to prove themselves, not just once, but multiple times, in a way that a special white man or mediocre white man may not have to.”

It’s not that women aren’t directing, writing, composing, and choreographing. Look just about anywhere but Broadway to see women crafting the buzzy, exciting new work that drives theatre forward. The issue is what makes it to Broadway. That becomes its own conversation about what is commercially viable. Director Leigh Silverman, whose work on The Lifespan of a Fact this season went overlooked at the Tonys, explains, “From my vantage point it seems that producers are looking for a director who is a strong, stable captain of their ship; a proven commodity that they believe will minimize their financial risk; and a leader who will weather high anxiety while staying creatively dexterous – traits generally thought to be associated with men.”

Female creative teams are inherently seen as financial risks for producers, who are ultimately the ones making decisions to bring shows to Broadway in hopes of making a profit. Add onto the stereotypes the fact that women are taking risks with theatrical form and content – much like Hadestown, with its unusual sound and unconventional source material. Women’s shows have to go through multiple out-of-town and off-Broadway tryouts and potentially even cast a celebrity to get enough momentum for Broadway producers to pick them up.

But when women and their risky shows do make it to Broadway, they become visible. They tell their stories and connect to voices in the crowd that are too often silenced. Their shows become more likely to go on tour, or pop up in regional theaters, or become someone’s favorite cast album. They become more likely to change lives and minds. Making it to Broadway forms a ripple effect throughout American theatre, jumpstarting change in what stories are told and how to tell them.

For me, as a female dramaturg/director/writer, it is the work of women that makes my eyes light up and feeds my dreams. It is their work that resonates with my personal experiences while expanding my understanding of what theatre can be – and what I can be.

I decided back in 2017 that I wanted to direct Hadestown one day and I doubt I ever would’ve had that impulse without knowing it was written and directed by women. Female creative teams are vital not just to tell their stories, but to invigorate the next generation of female creators like me. I look to Broadway’s lack of female creative teams not only as a disappointment but also as a problem I want to help solve.

When Broadway is so visible and so influential in the world of art, having female creative teams becomes deeply important – potentially, such teams could even be a way to break down some of the systemic inequality of genders. As for solutions? “It’s really simple. Gender parity can happen if people hire more women. That’s the answer,” says Silverman, addressing producers and artistic directors. “Hold yourself accountable. Do you have an interest in prioritizing gender parity?”

For female creative teams, the path to Broadway is long and uncertain. But it is a path worth going on, for women to tell their stories in new ways, to new people, for new times. Maybe this year Anaïs Mitchell and Rachel Chavkin will prove themselves at the Tony Awards with Hadestown. But even if they don’t, they’ve already made quite the impact.

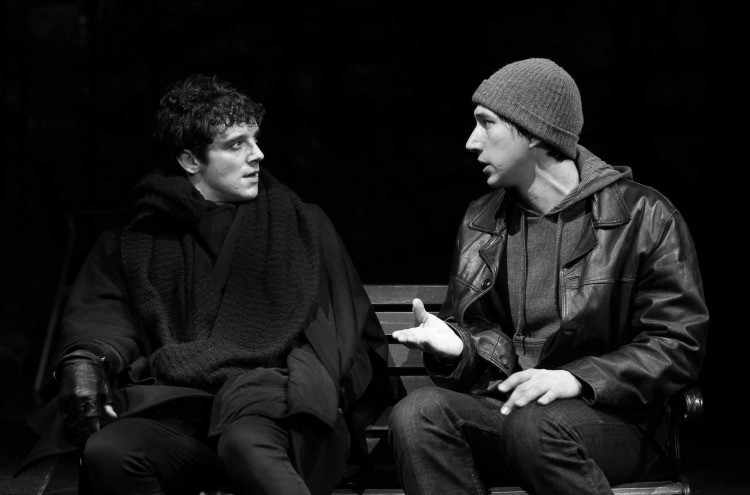

Director Rachel Chavkin looks on during a rehearsal for Hadestown. Photo by Matt Ross Public Relations.