Acting Identity

Acting is, at its simplest, the attempt to most accurately and authentically portray the experience of someone who is not you. An actor who grew up a Girl Scout may play a character who grew up a soccer player. An actor who is shy may play a character who is boisterous. An actor who is gay may play a character who is straight. An actor who is straight may play a character that is gay. Recently, I have confronted a range of opinions from straight and LGBT-identified actors about the appropriateness of straight actors playing LGBT characters. I want to begin this article by stating clearly that while I am, myself, LGBT-identified, I would also never wish to invalidate the feelings of others who may see this issue differently than me. I do, however, as an actor and playwright, find myself drawn to the overall question of where the line should be drawn, not only related to sexuality but also to other identities, abilities, and experiences. When is it okay for an actor who does not have that life experience to portray it on stage? When is it not?

First, as someone who began her career in theatre as an actor, I find myself inclined to believe that it is the actor’s job to communicate an experience and, indeed, an identity that is not their own. At its root, acting is performing something that looks true but isn’t. As my playwriting professor used to constantly remind us: “Drama often looks a lot like reality, but it isn’t reality. That’s why it’s drama.” In all my work in theatre, I tend to carry this notion with me. Therefore, I struggle with the idea that a straight actor cannot or should not play a character who is gay. There are multiple reasons for my disagreement with this statement. The first has to do with casting itself. In order for a director to cast gay actors in gay roles, they and/or the casting agents would have to ask actors to specify their sexual identity in order to audition which I firmly believe is invasive and inappropriate. Actors should not be expected to disclose their identities to get roles. Second, a character’s sexuality is only one piece of their identity, experience, and story. Should an actor truly be selected based on their personal identity and no other experience, emotional resonance, or talent? I, as a gay woman, have played plenty of straight women in my time as an actor. If one has an issue with straight actors playing gay characters, I feel as though they should have an issue with my playing straight characters, which no one ever has. Finally, to this point, the reason I love theatre so much is its ability to build empathy for the experiences of people who are not exactly like us. This empathy isn’t just created in the viewing audience, but also in the actor who endeavors to so completely understand their character’s thoughts, feelings, and expressions. To me, it seems restricting what identities and experiences actors can portray limits, too, the empathy that is it at the heart of what actors do.

Obviously, sexuality is only one of many different experiences, identities, and abilities that can be debated in terms of the actors that communicate them. Certainly, the theatre industry as a whole needs more actors of color, actors with disabilities, actors who are non-binary, the list could go on. These are complicated issues. I think we would all be remiss to believe there is any one solid answer to them. Sometimes, actors need to have certain experiences or identities to respectfully play a character; but, sometimes, if they do their research and enter the process with an open mind and heart, they can bring a character to life that is, perhaps, the antithesis of the actors themselves.

While actors, I believe, can and should be cast as characters with different identities from themselves if they are the best for the part, we also must be careful not to let actors from minority identities and experiences be excluded from telling their own stories, systematically or not. Again, it is a delicate balancing act that is in the hands of casting agencies, directors, and creative teams. It seems to me, however, that it should be more important to see playwrights and directors who are gay producing plays with gay characters and themes, or playwrights and directors who are disabled or transgender or autistic producing plays with those character experiences. Actors are a medium through which a story is told. In dramaturgical terms, characters are vessels for action. That is not to belittle the work of the actor by any means, but I do believe the creation and interpretation of the piece should rely more heavily on the input of those who understand the experience being relayed through the show. The story should be defined and told by those whose story it is. Unfortunately, I find playwrights and directors are subject to far less scrutiny than actors. It is somewhat understandable given that actors are the most visible element of a play, but I would implore critics to lend greater focus to these positions. It is up to the playwright and director to make sure stereotypes are not played and characters do not become offensive caricatures. That is their responsibility even more than the actors’ in most cases. Therefore, it is not simply the actor that must be considered in conversations on diversity in theatre, it is everyone: the designers, directors, playwrights, stagehands, dramaturgs. Theatre does not exist in a vacuum. It’s a team sport. Representation is too.

In the end, I can offer no specific solution to the important yet infinitely complex issue that is acting identity. All I can say is that it is something theatre-makers should continue to consider, even when it is difficult and the answers are not clear. If people voice their discomfort, listen. But I also implore those who are tempted to find anger to first speak with the actors they believe should not be playing a specific role. I find, often, there is more respect and empathy in their process than they are given credit for. And sometimes, they are disrespectful. Sometimes, they say or do the wrong thing. But just as learning lines is a process, so is learning a characterization. I truly believe in many cases, this can be an opportunity for us to learn from each other rather than divide ourselves further. We may find we are more alike than we thought.

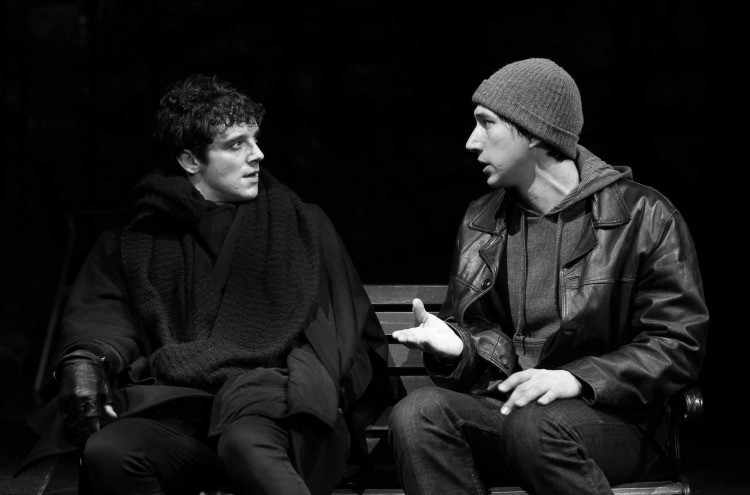

Photo by Ruca Souza.