West Side Stories - Jets vs Sharks or Nature vs Social Constructs?

After witnessing a white person accuse a US citizen of color of “not being American” on the Fourth of July a few years ago, this time of year always has me thinking about the social construction of race. In short, something that is socially constructed is an idea that humans create; it is not a naturally occurring biological fact.

With the Jets’ cultural amnesia about their families’ previous immigratation, non-white statuses, its team’s purposeful creation of racial markers through character and costume design, as well as the production’s history of racially fluid casting, what better musical is there to explore the social construction of race than West Side Story?

West Side Story

West Side Story opened in 1957. The film adaption followed shortly after in 1961. West Side Story’s spin on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet reflects the heightening racial tensions of the period it premiered in: instead of being caught between the conflict of the Capulets and the Montagues, the star-crossed lovers (Maria and Tony) are in the midst of a war between the Puerto Rican gang known as the Sharks and the white Jets.

The Jets’ Cultural Amnesia: Forgetting Eastern Europeans’ Immigrant and Non-White

Status

The animosities the Jets display towards the Sharks showcase the social construction of race. Such animosity stems from the Jets’ belief that they are fundamentally different: Jets are American—Sharks are not. Although nationality is different than race, being truly American is often equated with being white. This not only happens in the blatantly racist era West Side Story’s characters inhabit, but today as well. (As a Filipino American, I’m asked the all-too-often question of “No, where are you really from?)

But who is truly American? Broader still, who is truly white? Sure, the Sharks immigrated to America, but the Jets’ families most likely did the same a few generations back. 1880-1924 marked a period of high Eastern European immigration. What’s more, these Eastern Europeans (such as Polish immigrants) weren’t even considered white until the mid-20th century. Before then, they were regarded as an “other” race and faced discrimination (and after as well). As Bernardo (the Shark’s leader) and Anita (his girlfriend) animatedly discuss in a prelude to the energetically sung and danced “merica”, Tony is not some mythical white American from a family without an immigrant history—he is Polish. (“With an American, who is really a Polack!”) Just a few decades ago, Tony and the Jets would figuratively and literally be in the same boat as the Sharks.

Creating Racial Markers: Character and Costume Design

West Side Story’s character designs further illustrate that race is not a biological category. In a talk with NPR, Rita Moreno, who stars as Anita in the film, reveals how Jet cast members had to use very pale makeup and Hispanic cast members all had to wear the same shade of brown. The actors’ natural skin colors—the visual that is oft cited as proof of race’s realness—were completely disregarded. Instead, West Side Story’s team had to cover up what the actors’ bodies biologically produced in order to establish the groups’ racial difference.

The 2009 Broadway revival and its following tours also demonstrate how race is socially constructed. In this version, the Sharks are clothed in cool colors while the Jets wear warm yellows, oranges, and reds. Modifying the actors’ bodily markers are not enough to establish race: the explicitly arbitrary symbols of clothing colors unrelated to race are also needed to convey a supposedly natural difference. If race truly were a biological occurrence, West Side Story’s team would not have to go to such lengths to differentiate the two groups with human-created visuals. Seeing the natural appearance of the actors would be enough.

Racially Fluid Casting

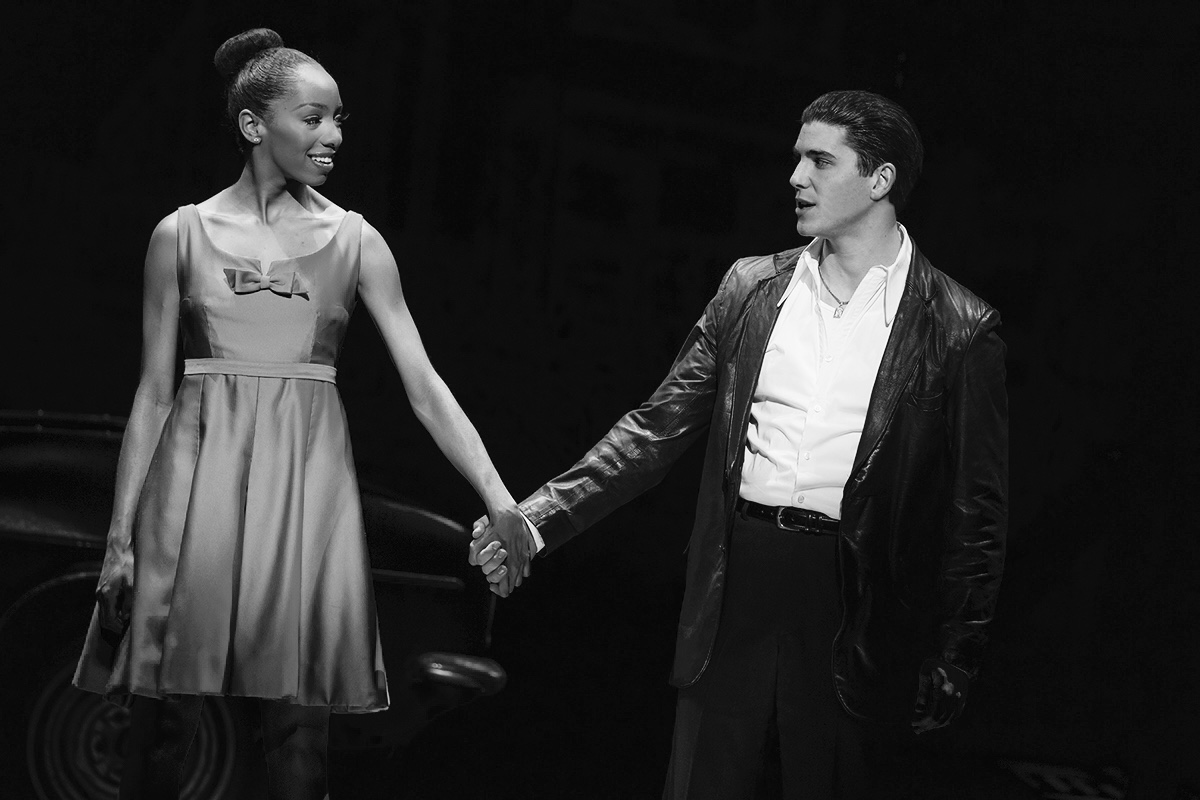

The character and costume designs are not unrelated to West Side Story’s racially fluid casting. In the 2013 US national tour cast, multiple understudies were listed as substituting for both Shark and Jet roles—all that was needed was a simple slip into a blue jacket and a white gang member became a Puerto Rican. Such casting applies to leads as well. George Chakiris, who plays Bernardo in the film, previously portrayed Riff, the Jets’ leader, in the London stage production.

The ability for actors to seamlessly switch between the two races illustrates that the idea of race is not a “black and white”—or brown and white—matter of truth.

Constructed category, Real Effects

Although we've talked about how West Side Story reveals that race is not “real” in the sense that it is not a naturally created product of biology, it is important to note that the effects of belonging in a racial category are real. Racist dynamics still exist today, even in the theatre community. Just earlier this year, Sierra Boggess, a white actress, was cast as Maria in a West Side Story concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall. In effect, Boggess beat out the highly underrepresented group of Latina actresses for the role. (Boggess has since respectfully withdrawn from the concert and apologized.)

That is not to say we should forget that race is socially constructed. Having such knowledge is crucial in dispelling the biological arguments used to justify racist ideology. And knowing that race is something we created, and that its detrimental effects are something we created as well, leads to the realization that our currently racist world is not a set-in-stone, “natural” way of life.

What we created, we can undo—“somehow, someday.”

(Photo credit: Creative Commons.)