Moby-Dick: Intentionally Messy, Exceedingly Ambitious - and Perfectly Imperfect Art

Warning: This review contains spoilers for the production.

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick is the Great American Novel everyone (except me for some reason) had to read in high school. You probably know the premise: young sailor Ishmael joins the motley crew of the whaling ship Pequod, captained by the maniacal Ahab, who seeks revenge on the titular white sperm whale who made off with his leg… and disaster eventually ensues as the ship and its crew meets its fate at the jaws of the great beast. A classic that’s way too long for most people to want to read for fun, full of bizarre and long-winded tangents no one cares about? Sounds like the perfect choice for musical theatre’s most gifted weirdo/classic lit enthusiast to adapt into a 3.5 hour, four-part musical theatre extravaganza.

If you had to ask me who my favorite musical theatre writer/director duo of all time is, it’d have to be Dave Malloy and Rachel Chavkin, the Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince of my generation. Time and time again the two of them, together and with other creatives, deliver art that absolutely destroys the boundaries of what a musical can be. A massive glittering electropop opera based on a 70 page slice of Leo Tolstoy’s doorstop novel War and Peace, staged immersively with a hyper diverse cast? Malloy and Chavkin’s Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812 delivered exactly that. Comet put the two of them on the map and was hailed as ahead of its time, but sadly closed too soon on Broadway. Malloy and Annie Tippe’s chamber choir musical Octet is an intimate, genre-defying meditation on internet addiction and mental health delivered through a stunning a cappella score; Chavkin finally won her Best Director for her masterful collaboration with Anais Mitchell on the moving, mythic Hadestown. Now, with their version of Moby-Dick, Dave Malloy and Rachel Chavkin have created a vision of America today colliding with America in the 1850s that’s as messy and ambitious as both the source material and the nation it’s embodying. Their “musical reckoning”, now playing at the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is an intentionally messy, exceedingly ambitious - and honestly, perfectly imperfect - work of theatre as ritual, art, communal experience, and entertainment.

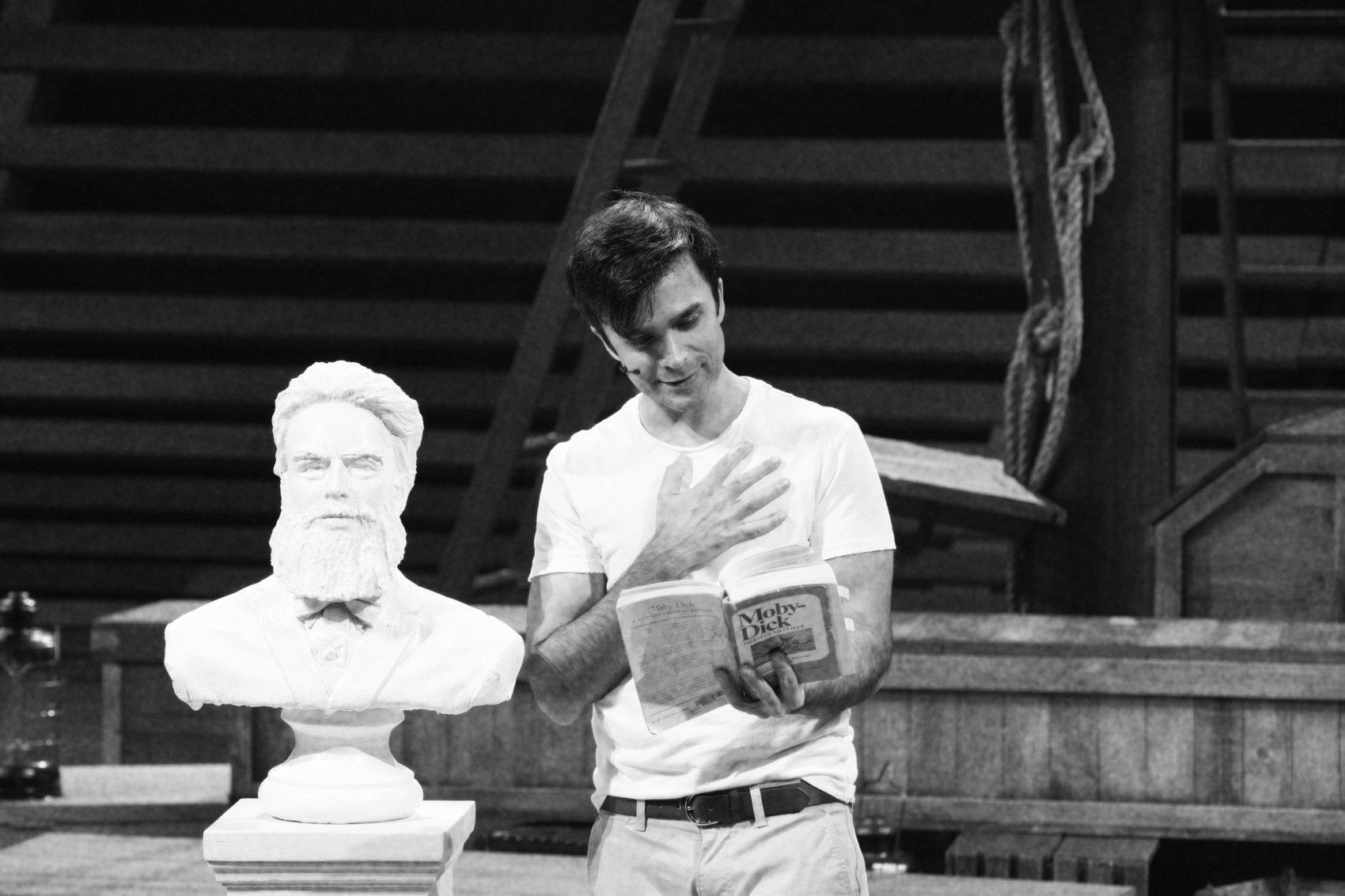

The evening begins with a sermon from Father Mapple (Dawn L. Troupe, in gorgeous voice and playing numerous characters throughout the show) retelling the biblical story of Jonah and the Whale. The sermon concludes, and we’re greeted by Ishmael, the young sailor that takes us along on our whaling journey as narrator, emcee, and audience surrogate. Ishmael is played by the wonderful Manik Choksi, who was so delightfully roguish as Fedya Dolokhov in Great Comet. Here, Choksi is an endearingly nerdy and empathetic hero with a truly lovely singing voice and great chemistry with his castmates. Ishmael begins the show in modern plainclothes, telling the audience of Herman Melville’s romantic interest in Nathaniel Hawthorne (whom the novel was dedicated to) and dreaming of casting the characters of Moby-Dick to represent the America he dreams about. Then he puts on a coat, leaps into the story and soon meets the crew of the Pequod: loyal first mate Starbuck (the stunning Starr Busby, so good in Octet); quirky second mate Stubb (delightful Kalyn West, making a total 180 from her work in The Prom); tough-as-nails third mate Flask (spiky Anna Ishida); tambourine-playing cabin boy Pip (a moving Morgan Siobhan Green, fresh from Be More Chill); the African harpooner Daggoo (J.D. Mollison, another excellent Octet alum); the Native American harpooner Tashtego (Matt Kizer, one to watch); and the Polynesian cannibal Queequeg (a captivating Andrew Cristi). Both here and in the original novel, Queequeg and Ishmael are bunkmates aboard the Pequod, and grow to be very close companions - the musical blessedly ramps this relationship up to the two becoming very tender lovers. (Relatedly, in this production Queequeg is costumed in a chest binder - not only are Ishmael and Queequeg lovers, Queequeg is trans in this production too!) Also aboard the ship are two more shipmates (former Balaga Ashkon Davaran and Octet alum/Shiz cast member Kim Blanck) providing gorgeous harmonies and musical assistance, and a Parsi prophet named Fedallah (the caustically funny Eric Berryman). The entire cast consists of actors of color, save for Captain Ahab - the white man after his white whale. Here, Ahab is played by the haunting Tom Nelis (who I loved in the older male track in Indecent) and is a terrifying, commanding presence.

With the entire crew of the ship assembled and Ahab’s mission to kill Moby-Dick made clear, the show transitions into the exciting but eventually doomed whaling voyage. Insuring the spirit of Melville is channeled throughout the show, entire tangents on cetology are taken straight from the book, and a whole section of the show is dedicated to the mental state of Pip the cabin boy after he falls off a whaling boat and is stranded alone in the ocean. To a lot of potential audience members, these sections might seem totally unnecessary and in need of trimming - but Rachel Chavkin is a gifted director and has created communal, ritualistic magic out of these seemingly unnecessary moments. The whaling section turns into some of the greatest examples of audience participation I’ve ever seen in 21 years of theatregoing, with audience members chosen during a pause between Parts One and Two to go on little boats on stage and join in on the bloody, fluid-splashing whale hunt. It’s like a theme park ride and experimental theatre had a baby - and it’s magical. The “Ballad of Pip” section is part spiritual journey, part deep-dive into the mind of this small child losing his mind, all directed so thrillingly and surreally. As the action concerns the lost Pip at center stage, the shiphands turn into angry channels of free verse, and the main crew play tambourine as backup. Another potentially unneeded but totally enthralling diversion comes in the middle of part two, where Fedallah breaks the fourth wall to deliver a blistering standup routine on the state of race in the United States as well as in the theatre. It’s hilarious and deeply, necessarily uncomfortable. In other creatives’ hands this section might feel wrong or “fake woke,” but Chavkin and Malloy are adamant champions of diversity in their work, and have dealt with their fair share of controversy (Comet’s premature end, which is too sore an issue to delve into further,) so it feels earned. The two of them have such shared visions as creatives and as humans that some parts of the show feel like commentary on their careers up to now. This show is a risk, and it’s a playground for two of the most daring artists in the business to see what sticks. Rachel is a master at work, and these controversial sections of the musical work so damn well because her vision is so clear and her synergy with Dave’s book and score is so palpable.

Musical styles, like Melville’s original writing, jump all over the place in Moby-Dick. Part One is classic Malloy introduction and character development songs, Part Two is a full on vaudeville spanning all the notoriously meandering chapters on whaling and whale facts, Part Three is a half-hour jazz/hip-hop cycle, and Part Four is a somber, full-throttle thrill ride spanning even more song styles, including African polyrhythms. The score on paper might feel like a hodgepodge of genres, but there are enough repeated melodies and themes for certain characters that crop up throughout the score tying everything all together. Dave Malloy is my favorite modern musical theatre writer and this score contains an embarrassment of riches in its songs. Malloy’s musicals often have deeply earwormy opening numbers (“Prologue” from Great Comet, anyone?) and Moby-Dick’s opening song, “The Sermon,” certainly gets in your head with its plot-foretelling lyrics (“We are all in the belly of the whale/hiding in the dark from the sins that tell our tale/And the darkness will take us down/’Less we speak truth to power/Only then will we be free/you and me, hand in hand on a coffin/Drifting on the sea.”) In Part One, Queequeg gets a jaunty song about why his cannibalism shouldn’t be frowned upon (“A Bosom Friend”) and a tender, romantic duet with Ishmael in Part Four (“The Pacific”) that stands as one of Malloy’s best standalone musical theatre songs in addition to being so beautiful in context. During the whaling vaudeville, we get a gleefully geeky cabaret song from Ishmael about how to categorize whales (“Cetology”), a fun charm song from Stubb about the pleasure of eating whales (“The Whale As A Dish”), and a lovely communal hymn about the hypnotic, borderline homoerotic pleasure of squeezing spermaceti with the crew (“A Squeeze of the Hand”). Ahab gets a soliloquy song (“Sunset”) that echoes the loneliness of Pierre in Great Comet; Starbuck gets a heartbreaking solo (“Dusk”) debating how far he’s willing to go along with with the captain’s certainly-doomed revenge mission. The entire “Ballad of Pip” cycle is a thrilling, spoken word/jazz explosion that is hilarious, utterly baffling at times, and totally heartbreaking and poignant.

I first got the opportunity to hear about a third of this score in July at a special concert of excerpts held under the blue whale at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. I was enraptured by what parts of the score I heard then, but finally hearing it all in full context of the staged production it all truly came together. Or Matias, the music director on Great Comet, is back for Moby-Dick, and the cast sings this difficult music with absolute ease thanks to his work. This score is immense, challenging, rangy, endlessly inventive and surprising. Random snatches of melody and lyrics from this score get stuck in my head even when I’m not thinking about the show - that’s how powerful the music of this musical is. I need a cast recording yesterday. Every time Dave Malloy writes a new score, you never know what to expect, and it’s always great. He’s the future of musical theatre writing, always tackling the most unexpected source materials and crafting gorgeously layered and surprising music to tell those stories.

A musical isn’t complete without its technical elements. Moby-Dick reunites Malloy and Chavkin with some of their Comet collaborators as well as new creatives bringing their visions to the table. Mimi Lien’s stunning set is entirely wooden and flows naturally to cover the entire proscenium thrust area; all at once it brings to mind both the deck of a whaling ship and the ribs of a whale. Lien’s set is gorgeously lit by Bradley King’s lighting designs - and of course, being a Bradley King-designed show, a massive wall of lights on the back wall of the stage proves a major coup-de-theatre during the climactic sea battle with the title whale. If you’ve seen Great Comet or Hadestown, you may recall the bursts of light forming the entrances of Anatole and Hades - the great white whale joins those iconic character entrances to create a holy trinity of Bradley King lighting magic. Sound design by Hidenori Nakajo uses ambient ocean noise and whalesong to set the scenes aurally. The Cetology section of the whaling vaudeville in Part Two of the show is aided by Eric Avery’s delightful whale puppets made from found and recycled objects. Chanel DeSilva provides tight, vibrant choreography. Brenda Abbandandolo’s costumes are a gorgeous hybrid of modern dress and period touches (historically accurate harpoons, tribal clothes for Tashtego and Queequeg) that complement the anachronistic vibes the show gives off. Technically, the show works like a dream in the Loeb, feeling intimate and immersive in a moderately sized performance space - if it were to move to New York City I could easily envision it in the Park Avenue Armory, St. Ann’s Warehouse, or the largest performance space the Public Theater has. (And, ideally, the Circle in the Square when it gets to Broadway.) The show is massive at heart, and deserves a massive space to tell its story.

Dave Malloy and Rachel Chavkin’s Moby-Dick: A Musical Reckoning is proof that lightning can strike more than once for the truly greatest musical theatre visionaries. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen in theatre, musical or otherwise. I saw the show twice in one day, and with a 3 and a half hour runtime, I left Cambridge that evening physically exhausted but deeply, soulfully satisfied. It’s certainly not a musical for everyone - Melville purists might scoff, and those not willing to embrace the audacity will probably leave confused and insulted. But me? I loved it. I loved it almost as much as I loved Hadestown. Would I change anything? Maybe I’d make the romance between Ishmael and Queequeg even more evident, but there’s nothing I personally want to see cut - it needs the exact brand of massive, controlled messiness it already has to get its vision of America as a whaling ship across. Moby-Dick at the ART is insane, tonally all over the place, wild, and absolutely brilliant - one of the best pure theatregoing experiences I’ll probably ever experience as long as I live. If you can find a way to get aboard the Pequod, go. It’ll change the way you think about what’s possible in the arts. I can’t wait to see where this white whale goes next. Dave Malloy and Rachel Chavkin, thank you so much.

Photo by Evgenia Eliseeva.